The Story of Lime

Creating architectural surfaces built on tradition and heritage is our art and science. Here we share with you the history, the practicality, and the manufacturing process of lime.

Beautiful. Soft. Luminescent.

The ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, Rome, China, Japan, and Mesoamerica built structures of lime that stand today. Lime exudes a natural, soft, iridescent, almost translucent depth of color so that light seems to go deeper than in modern cements and finishes.

Practical. Durable. Flexible.

Beyond it’s natural beauty, limestone is a pragmatic material. It breaths. It withstands damp, wet climates. It’s alkalinity makes it naturally mold and mildew resistant. It’s easy to patch while fresh, and during construction, it can naturally fill in small cracks that might form. It’s produced without harmful chemicals or byproducts.

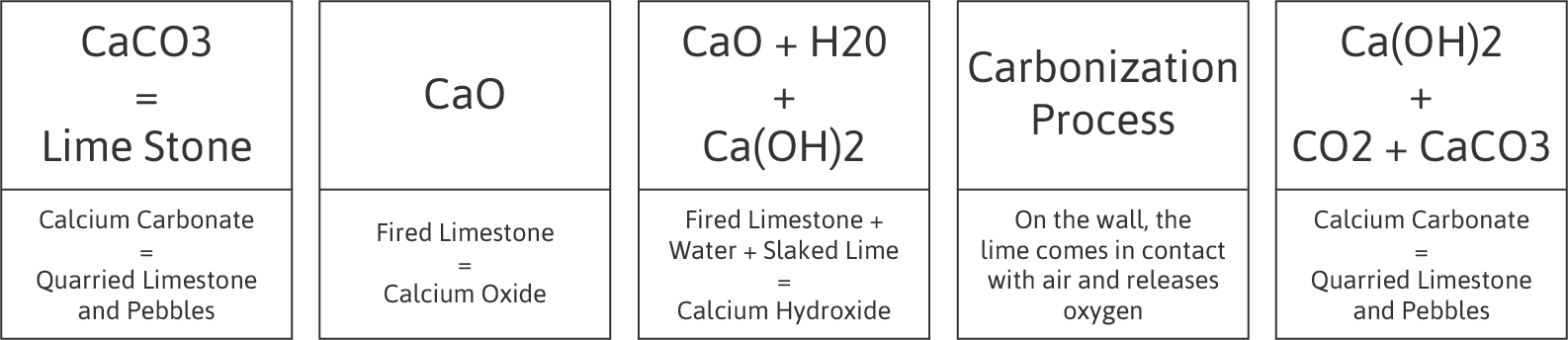

The Chemical Process

It starts as limestone. It ends as limestone.

The Lime Source

River pebbles and quarried lime, rich in calcium carbonate, are transformed into aged slaked lime putty. Dating back to the ancient Greek and Phoenician civilizations, lime’s durability and subtle beauty has carried it from the Old World into the New. This renewable, naturally occurring substance combined with modern technology has proven itself among the most resistant, aesthetic, and ecological building materials available on the market today.

Baking

During the baking process, ancient custom and innovation merge. Although the traditional brick barrel furnaces are still used, a computerized control system overseas each stage – from when the limestone first enters the furnaces until the process is complete a week later. The temperature is kept stable with the continuous addition of sawdust; highly sophisticated lasers purify the combustion fumes before they are released into the atmosphere.

Slaking

The result of the baking process is quicklime. During the slaking stage, water is added to the material. This creates a dense liquid which is thoroughly filtered for any unbaked particles that could critically damage the quality of the final product. After the straining process is complete, the purified quicklime is sent to large tanks – the next stage in the slaked lime process.

Aging

The aging process occurs in a large 500-ton-pit. To achieve the aged, authentic look of slaked lime it is imperative that the material set within the enclosure for at least six months. During this time, the product’s chemical structure is altered to create the unique texture and appearance of aged slaked lime.

Filtration

Before the final stage of the manufacturing process begins, the slaked lime is micro-filtered to ensure a creamy, smooth material free from impurities.

The Final Step: Pigmentation

As carbonate crystals dry, they form a hard, invisable crust on the surface, which solidly binds to pigments. Thus, the color becomes an integral part of the plaster as is seen in Bueno frescoes done over wet lime putty. This chemical process is what makes lime plasters last and keeps the colors vibrant for decades, even centuries.